Pancreatitis

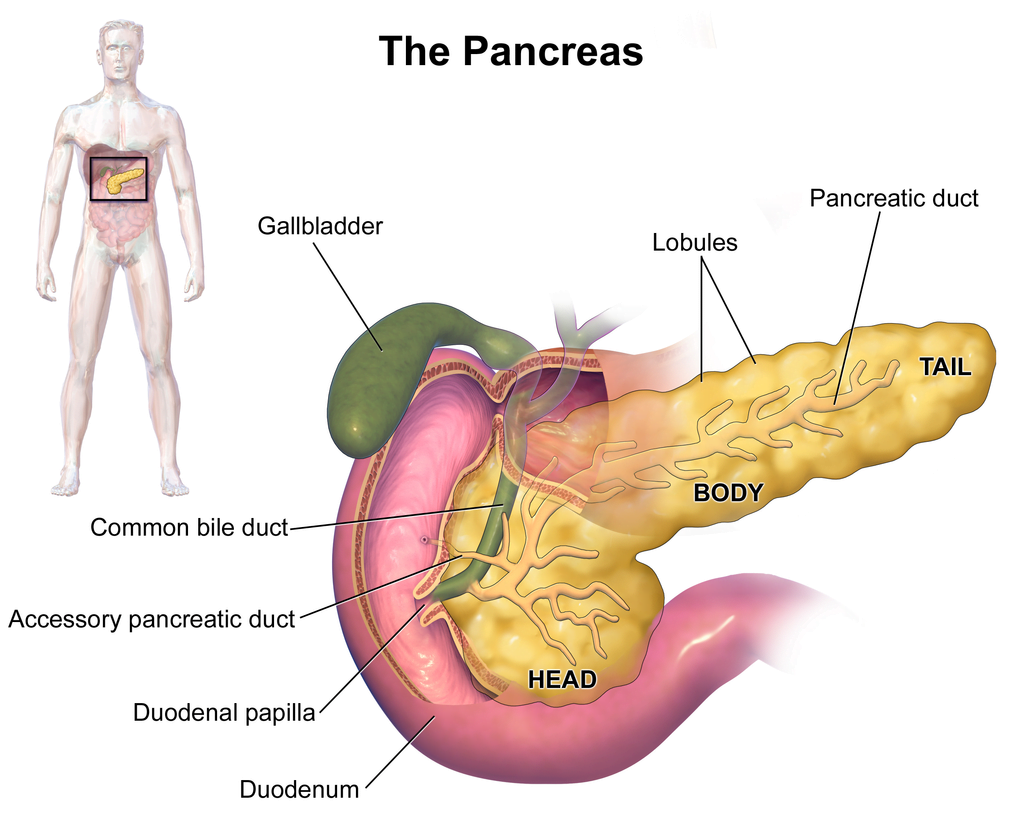

Pancreatitis is an inflammation of the pancreas. The pancreas is a large gland behind the stomach and close to the duodenum. The duodenum is the upper part of the small intestine. The pancreas secretes digestive enzymes into the small intestine through a tube called the pancreatic duct. These enzymes help digest fats, proteins, and carbohydrates in food. The pancreas also releases the hormones insulin and glucagon into the bloodstream. These hormones help the body use the glucose it takes from food for energy.

Normally, digestive enzymes do not become active until they reach the small intestine, where they begin digesting food. But if these enzymes become active inside the pancreas, they start digesting the pancreas itself. This process is called autodigestion and causes swelling, haemorrhage, and damage to the blood vessels. An attack may last for 2 days

- Acute pancreatitis occurs suddenly and lasts for a short period of time and usually resolves. Acute pancreatitis is usually caused by drinking too much alcohol or by gallstones. A gallstone can block the pancreatic duct, trapping digestive enzymes in the pancreas and causing pancreatitis.

- Chronic pancreatitis does not resolve itself and results in a slow destruction of the pancreas. Chronic pancreatitis occurs when digestive enzymes attack and destroy the pancreas and nearby tissues. Chronic pancreatitis is usually caused by many years of alcohol abuse, excess iron in the blood, and other unknown factors. However, it may also be triggered by only one acute attack, especially if the pancreatic ducts are damaged.

- Either form can cause serious complications. In severe cases, bleeding, tissue damage, and infection may occur. Pseudocysts, accumulations of fluid and tissue debris, may also develop. And enzymes and toxins may enter the bloodstream, injuring the heart, lungs, and kidneys, or other organs.

Acute pancreatitis generally causes severe pain and the sufferer will need emergency treatment in a hospital. Pancreatitis is generally diagnosed quickly, by examination of the abdomen, and confirmed using a series of medical tests, including:

- General tests – such as blood tests, physical examination and x-rays

- Ultrasound – sound waves form a picture that detects the presence of gallstones

- CT scan – a specialised x-ray takes three-dimensional pictures of the pancreas

Some of the complications from pancreatitis are: low blood pressure, heart failure, kidney failure, ARDS (adult respiratory distress syndrome), diabetes, ascites (accumulation of fluid in the abdomen) and cysts or abscesses in the pancreas.

Acute pancreatitis

- Hospital care – in all cases of acute pancreatitis

- Intensive care in hospital – in cases of severe acute pancreatitis

- Fasting and intravenous fluids – until the inflammation settles down

- Endoscopy – a thin tube is inserted through your oesophagus to allow the doctor to see your pancreas

- Surgery – if gallstones are present, removing the gallbladder will help prevent further attacks. In rare cases, surgery is needed to remove damaged or dead areas of the pancreas

- Lifestyle change – eliminating alcohol

Chronic pancreatitis

- Lowering fat intake

- Supplementing digestion by taking pancreatic enzyme tablets with food

- Eliminating alcohol

- Insulin injections, if the endocrine function of the pancreas is compromised

- Analgesics for pain

Pancreatic cancer

Pancreatic cancer occurs when abnormal cells within the pancreas grow in an uncontrolled way. The pancreas is a small gland that sits behind the stomach.1 It produces hormones, such as insulin, that control sugar levels in the blood.

The pancreas also produces enzymes that help the body digest food.

There are two different types of pancreatic cancer.

- Exocrine tumours develop in the cells in the pancreas that produce digestive enzymes. More than 90 per cent of all pancreatic cancers are exocrine tumours.

- Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours (also called islet cell tumours) are rarer cancers that develop in the cells in the pancreas that produce hormones.

This fact sheet is about pancreatic exocrine tumours.

There are often no symptoms of pancreatic cancer in the early stages of the disease. The most common symptoms of pancreatic cancer are:

- yellowing of the skin and the whites of the eyes – this is

called jaundice - pain in the upper or middle back or abdomen

- unexplained weight loss

- loss of appetite

- unusual tiredness.

There are a number of conditions that may cause these symptoms, not just pancreatic cancer. If any of these symptoms are experienced, it is important that they are discussed with a doctor.

A risk factor is any factor that is associated with an increased chance of developing a particular health condition, such as pancreatic cancer. There are different types of risk factors, some of which can be modified and some which cannot. It should be noted that having one or more risk factors does not mean a person will develop pancreatic cancer. Many people have at least one risk factor but will never develop pancreatic cancer, while others with pancreatic cancer may have had no known risk factors. Even if a person with pancreatic cancer has a risk factor, it is usually hard to know how much that risk factor contributed to the development of their disease.

While the causes of pancreatic cancer are not fully understood, there are a number of factors associated with the risk of developing the disease. These factors include:

- tobacco smoking

- chronic inflammation of the pancreas – called pancreatitis

- certain inherited genetic conditions such as hereditary pancreatitis syndrome, Lynch Syndrome, hereditary atypical multiple mole melanoma syndrome, hereditary BRCA2-related breast and ovarian cancer and Peutz-Jeghers syndrome

- long-term diabetes (Type 2)

A number of tests will be performed to investigate symptoms of pancreatic cancer and confirm a diagnosis. Some of the more common tests include:

- a physical examination

- imaging of the abdomen , which may include X-ray, computed tomography (CT) scan endoscopic ultrasound

(for small tumours)3 or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) - an internal examination of the organs inside the abdomen using endoscopy or laparoscopy1

- taking a sample of tissue (biopsy) from the pancreas for examination under a microscope.1

Treatment and care of people with cancer is usually provided by a team of health professionals – called a multidisciplinary team. Treatment for pancreatic cancer depends on the stage of the disease, the severity of symptoms and the person’s general health. Treatment options can include surgery to remove part or all of the pancreas and nearby organs that may be affected, radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy, and targeted therapies to destroy cancer cells.1,2 Research is ongoing to find new ways to diagnose and treat different types of cancer. Some people may be offered the option of participation in a clinical trial to test new ways of treating pancreatic cancer.

People often feel overwhelmed, scared, anxious and upset after a diagnosis of cancer. These are all normal feelings.Having practical and emotional support during and after diagnosis and treatment for cancer is very important. Support may be available from family and friends, health professionals or special support services. In addition, State and Territory Cancer Councils provide general information about cancer as well as information on local resources and relevant support groups. The Cancer Council Helpline can be accessed from anywhere in Australia by calling 13 11 20 for the cost of a local call.

More information about finding support can be found on the Cancer Australia website www.canceraustralia.gov.au

Splenectomy

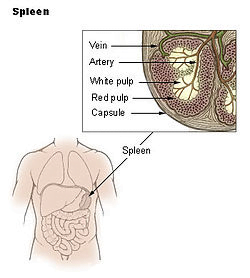

The spleen is a blood filled organ located in the upper left abdominal cavity. It is a storage organ for red blood cells and contains many specialized white blood cells called “macrophages” (disease fighting cells) which act to filter blood. The spleen is part of the immune system and also removes old and damaged blood particles from your system. The spleen helps the body identify and kill bacteria. The spleen can affect the platelet count, the red blood cell count and even the white blood count.

There are several reasons why a spleen might need to be removed, and the following list, though not all inclusive, includes the most common reasons. The most common reason is a condition called idiopathic (unknown cause) thrombocytopenia (low platelets) purpura (ITP). Platelets are blood cells which aid is blood clotting. Haemolytic anaemia (a condition that breaks down red blood cells) requires a spleen removal to prevent or decrease the need for transfusion. Also, hereditary (genetic) conditions that affect the shape of red blood cells, conditions known as spherocytosis, sickle cell disease or thalassemia, may require splenectomy. Often patients with cancers of the cells which fight infection, known as lymphoma or certain types of leukaemia, require spleen removal. When the spleen gets enlarged, it sometimes removes too many platelets from your blood and has to be removed. Sometimes the spleen is removed to diagnose or treat a tumour. Sometimes the blood supply to the spleen becomes blocked (infarct) or the artery abnormally expands (aneurysm) and the spleen needs to be removed.

An evaluation typically includes a full blood examination (FBE), a visual look at the blood cells placed on a glass slide called a ‘smear’, and often a bone marrow examination. Sometimes an ultrasound examination of your spleen, a computerized tomography (CT scan), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or nuclear scan is needed.

Results may vary depending on your overall condition and health. Usual advantages are:

- Less postoperative pain

- Shorter hospital stay

- Faster return to a regular, solid food diet

- Quicker return to normal activities

- Better cosmetic results

Most patients can have a laparoscopic splenectomy. Though the experience of the surgeon is the biggest factor in a successful outcome, the size of the spleen is the most important determinant in deciding whether the spleen can be removed laparoscopically. When the size of the spleen is extremely large, it is difficult to perform the laparoscopic technique. Sometimes, plugging the artery to the spleen right before surgery using special X-ray technology can shrink the spleen to allow the laparoscopic technique. You should obtain a thorough evaluation by a surgeon qualified in laparoscopic spleen removal along with consultation with your other physicians to find out if this technique is appropriate for you.

- After your surgeon reviews with you the potential risks and benefits of the operation, you will need to provide written consent for surgery.

- Preoperative preparation includes blood work, medical evaluation, chest x-ray and an ECG depending on your age and medical condition.

- Immunization with a vaccine to help prevent bacterial infections after the spleen is removed should be given two weeks before surgery, if possible.

- Blood transfusion and/or blood products such as platelets may be needed depending on your condition.

- Your surgeon may request that you completely empty your colon and cleanse your intestines prior to surgery. You may be requested to drink clear liquids, only, for one or several days prior to surgery.

- It is recommended that you shower the night before or morning of the operation.

- After midnight the night before the operation, you should not eat or drink anything except medications that your surgeon has told you are permissible to take with a sip of water the morning of surgery.

- Drugs such as aspirin, blood thinners, anti-inflammatory medications (arthritis medications) and Vitamin E will need to be stopped temporarily for several days to a week prior to surgery.

- Diet medication or St. John’s Wort should not be used for the two weeks prior to surgery.

- Quit smoking and arrange for any help you may need at home.

You will be placed under general anaesthesia and be completely asleep. A cannula (hollow tube) is placed into the abdomen by your surgeon and your abdomen will be inflated with carbon dioxide gas to create a space to operate. A laparoscope (a tiny telescope connected to a video camera) is put through one of the cannulas which projects a video picture of the internal organs and spleen on a television monitor. Several cannulas are placed in different locations on your abdomen to allow your surgeon to place instruments inside your belly to work and remove your spleen. A search for accessory (additional) spleens and then removal of these extra spleens will be done since 15% of people have small, extra spleens. After the spleen is cut from all that it is connected to, it is placed inside a special bag. The bag with the spleen inside is pulled up into one of the small, but largest incisions on your abdomen. The spleen is broken up into small pieces (morcelated) within the special bag and completely removed.

In a small number of patients the laparoscopic method cannot be performed. Factors that may increase the possibility of choosing or converting to the “open” procedure may include obesity, a history of prior abdominal surgery causing dense scar tissue, inability to visualize organs or bleeding problems during the operation.

The decision to perform the open procedure is a judgment decision made by your surgeon either before or during the actual operation. When the surgeon feels that it is safest to convert the laparoscopic procedure to an open one, this is not a complication, but rather sound surgical judgment. The decision to convert to an open procedure is strictly based on patient safety.

References

1. National Cancer Institute. Pancreatic cancer treatment (PDQ) – patient version. Available from http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/pancreatic/ Patient. [Accessed July 2012].

2. Thomson B. Pancreatic cancer: current management. Australian Family Physician 2006; 34(4): 212–216.

3. Pancreatic cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up Annals of Oncology 2010.