Colorectal & Perianal

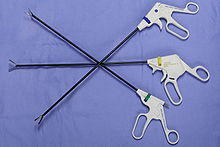

Laparoscopy

Laparoscopy is commonly performed procedure to investigate and perform some keyhole surgeries on abdominal and pelvic organs.

Laparoscopy is direct visualization of the abdominal cavity, ovaries, outside of the tubes and uterus by using a laparoscopy. The laparoscope is a long thin instrument with a light source at its tip, to light up the inside of the abdomen or pelvis. Fibreoptic fibres carry images from a lens, also at the tip of the instrument, to a video monitor, which the surgeon and other theatre staff can view in real time.

Laparoscopic Colorectal Surgery

Laparoscopic or “minimally invasive” surgery is a specialized technique for performing surgery. In the past, this technique was commonly used for gynecologic surgery and for gall bladder surgery. Over the last 10 years the use of this technique has expanded into intestinal surgery. In traditional “open” surgery the surgeon uses a single incision to enter into the abdomen. Laparoscopic surgery uses several 0.5-1cm incisions. Each incision is called a “port.” At each port a tubular instrument known as a trochar is inserted. Specialized instruments and a special camera known as a laparoscope are passed through the trochars during the procedure. At the beginning of the procedure, the abdomen is inflated with carbon dioxide gas to provide a working and viewing space for the surgeon. The laparoscope transmits images from the abdominal cavity to high-resolution video monitors in the operating room. During the operation the surgeon watches detailed images of the abdomen on the monitor. This system allows the surgeon to perform the same operations as traditional surgery but with smaller incisions.

In certain situations a surgeon may choose to use a special type of port that is large enough to insert a hand. When a hand port is used the surgical technique is called “hand assisted” laparoscopy. The incision required for the hand port is larger than the other laparoscopic incisions, but is usually smaller than the incision required for traditional surgery.

Compared to traditional open surgery, patients often experience less pain, a shorter recovery, and less scarring with laparoscopic surgery.

Most intestinal surgeries can be performed using the laparoscopic technique. These include surgery for Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, diverticulitis, cancer, rectal prolapse and severe constipation.

In the past there had been concern raised about the safety of laparoscopic surgery for cancer operations. Recently several studies involving hundreds of patients have shown that laparoscopic surgery is safe for certain colorectal cancers.

Laparoscopic surgery is as safe as traditional open surgery. At the beginning of a laparoscopic operation the laparoscope is inserted through a small incision near the belly button (umbilicus). The surgeon initially inspects the abdomen to determine whether laparoscopic surgery may be safely performed. If there is a large amount of inflammation or if the surgeon encounters other factors that prevent a clear view of the structures the surgeon may need to make a larger incision in order to complete the operation safely.

Any intestinal surgery is associated with ¬certain risks such as complications related anaesthesia and bleeding or infectious complications. The risk of any operation is determined in part by the nature of the specific operation. An individual’s general heath and other medical conditions are also factors that affect the risk of any operation. You should discuss with your surgeon your individual risk for any operation.

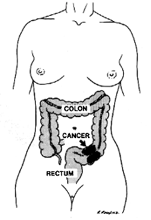

Colorectal Cancer

Colorectal cancer is the second most common cancer. It is potentially curable if diagnosed in the early stages.

Though colorectal cancer may occur at any age, more than 90% of the patients are over age 40, at which point the risk doubles every ten years. In addition to age, other high risk factors include a family history of colorectal cancer and polyps and a personal history of ulcerative colitis, colon polyps or cancer of other organs, especially of the breast or uterus.

It is generally agreed that nearly all colon and rectal cancer begins in benign polyps. These pre-malignant growths occur on the bowel wall and may eventually increase in size and become cancer. Removal of benign polyps is one aspect of preventive medicine that really works!

The most common symptoms are rectal bleeding and changes in bowel habits, such as constipation or diarrhoea. (These symptoms are also common in other diseases so it is important you receive a thorough examination should you experience them.) Abdominal pain and weight loss are usually late symptoms indicating possible extensive disease.

Unfortunately, many polyps and early cancers fail to produce symptoms. Therefore, it is important that your routine physical includes colorectal cancer detection procedures once you reach age 50.

There are several methods for detection of colorectal cancer. These include digital rectal examination, a chemical test of the stool for blood, flexible sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy (lighted tubular instruments used to inspect the lower bowel) and barium enema. Be sure to discuss these options with your surgeon to determine which procedure is best for you. Individuals who have a first-degree relative (parent or sibling) with colon cancer or polyps should start their colon cancer screening at the age of 40.

Colorectal cancer requires surgery in nearly all cases for complete cure. Radiation and chemotherapy are sometimes used in addition to surgery. Between 80-90% are restored to normal health if the cancer is detected and treated in the earliest stages. The cure rate drops to 50% or less when diagnosed in the later stages. Thanks to modern technology, less than 5% of all colorectal cancer patients require a colostomy, the surgical construction of an artificial excretory opening from the colon.

Colon cancer is preventable. The most important step towards preventing colon cancer is getting a screening test. Any abnormal screening test should be followed by a colonoscopy. Some individuals prefer to start with colonoscopy as a screening test.

Colonoscopy provides a detailed examination of the bowel. Polyps can be identified and can often be removed during colonoscopy.

Though not definitely proven, there is some evidence that diet may play a significant role in preventing colorectal cancer. As far as we know, a high fibre, low fat diet is the only dietary measure that might help prevent colorectal cancer.

Finally, pay attention to changes in your bowel habits. Any new changes such as persistent constipation, diarrhoea, or blood in the stool should be discussed with your physician.

No, but haemorrhoids may produce symptoms similar to colon polyps or cancer. Should you experience these symptoms, you should have them examined and evaluated by a physician, preferably by a colon and rectal surgeon.

Laparoscopic Colon Resection

Each year hundreds of thousands of surgical procedures are performed to treat a number of colon diseases. Although surgery is not always a cure, it is often the best way to stop the spread of disease and alleviate pain and discomfort.

Patients undergoing colon surgery often face a long and difficult recovery because the traditional “open” procedures are highly invasive. In most cases, surgeons are required to make a long incision. Surgery results in an average hospital stay of a week or more and usually 6 weeks of recovery.

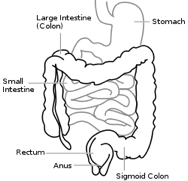

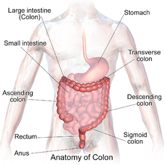

The colon is the large intestine; it is the lower part of your digestive tract. The intestine is a long, tubular organ consisting of the small intestine, the colon (large intestine) and the rectum, which is the last part of the colon. After food is swallowed, it begins to be digested in the stomach and then empties into the small intestine, where the nutritional part of the food is absorbed. The remaining waste moves through the colon to the rectum and is expelled from the body. The colon and rectum absorb water and hold the waste until you are ready to expel it.

A technique known as minimally invasive laparoscopic colon surgery allows surgeons to perform many common colon procedures through small incisions. Depending on the type of procedure, patients may leave the hospital in a few days and return to normal activities more quickly than patients recovering from open surgery.

In most laparoscopic colon resections, surgeons operate through 4 or 5 small openings (each about a quarter inch) while watching an enlarged image of the patient’s internal organs on a television monitor. In some cases, one of the small openings may be lengthened to 2 or 3 inches to complete the procedure.

Results may vary depending upon the type of procedure and patient’s overall condition. Common advantages are:

- Less postoperative pain

- May shorten hospital stay

- May result in a faster return to solid-food diet

- May result in a quicker return of bowel function

- Quicker return to normal activity

- Improved cosmetic results

Although laparoscopic colon resection has many benefits, it may not be appropriate for some patients. Obtain a thorough medical evaluation by a surgeon qualified in laparoscopic colon resection in consultation with your primary care physician to find out if the technique is appropriate for you.

Most diseases of the colon are diagnosed with one of two tests: a colonoscopy or barium enema. A colonoscope is a soft, bendable tube about the thickness of the index finger which is inserted into the anus and then advanced through the entire large intestine. A barium enema is a special X-ray where a white “milk-shake fluid” is flushed into the rectum and by using mild pressure is pushed throughout the entire large intestine. These tests allow the surgeon to look inside of the colon. Sometimes a CT scan of the abdomen will be necessary. Prior to the operation, other blood tests, electrocardiogram (ECG) or a chest x-ray might be required.

- Preoperative preparation includes blood work, medical evaluation, chest x-ray and an ECG depending on your age and medical condition.

- After your surgeon reviews with you the potential risks and benefits of the operation, you will need to provide written consent for surgery.

- Blood transfusion and/or blood products may be needed depending on your condition.

- It is recommended that you shower the night before or morning of the operation.

- The rectum and colon must be completely empty before surgery. Usually, the patient must drink a special cleansing solution. You may be on several days of clear liquids, laxatives and enemas prior to the operation.

- Antibiotics by mouth are commonly prescribed. Your surgeon or his/her staff will give you instructions regarding the cleansing routine to be used.

- Follow your surgeon’s instructions carefully. If you are unable to take the preparation or the antibiotics, contact your surgeon.

- If you do not complete the preparation, it may be unsafe to undergo the surgery and it may have to be rescheduled.

- After midnight the night before the operation, you should not eat or drink anything except medications that your surgeon has told you are permissible to take with a sip of water the morning of surgery.

- Drugs such as aspirin, blood thinners, anti-inflammatory medications (arthritis medications) and Vitamin E will need to be stopped temporarily for several days to a week prior to surgery.

- Diet medication or St. John’s Wort should not be used for the two weeks prior to surgery.

- Quit smoking and arrange for any help you may need at home.

“Laparoscopic” surgery describes the techniques a surgeon uses to gain access to the internal surgery site.

Most laparoscopic colon procedures start the same way. Using a cannula (a narrow tube-like instrument), the surgeon enters the abdomen. A laparoscope (a tiny telescope connected to a video camera) is inserted through the cannula, giving the surgeon a magnified view of the patient’s internal organs on a television monitor. Several other cannulas are inserted to allow the surgeon to work inside and remove part of the colon. The entire procedure may be completed through the cannulas or by lengthening one of the small cannula incisions.

A number of patients the laparoscopic method cannot be performed. Factors that may increase the possibility of choosing or converting to the “open” procedure may include:

- Obesity

- A history of prior abdominal surgery causing dense scar tissue

- Inability to visualize organs

- Bleeding problems during the operation

- Large tumours

The decision to perform the open procedure is a judgment decision made by your surgeon either before or during the actual operation. When the surgeon feels that it is safest to convert the laparoscopic procedure to an open one, this is not a complication, but rather sound surgical judgment. The decision to convert to an open procedure is strictly based on patient safety

Diverticular Disease

Diverticulosis of the colon is a common condition that afflicts about 50 percent of Americans by age 60 and nearly all by age 80. Only a small percentage of those with diverticulosis have symptoms, and even fewer will ever require surgery.

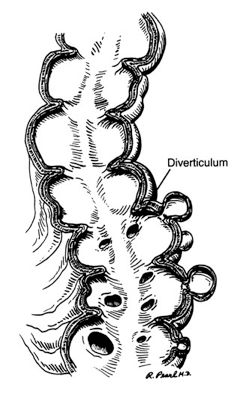

Diverticula are pockets that develop in the colon wall, usually in the sigmoid or left colon, but may involve the entire colon. Diverticulosis describes the presence of these pockets. Diverticulitis describes inflammation or complications of these pockets.

Uncomplicated diverticular disease is usually not associated with symptoms. Symptoms are related to complications of diverticular disease including diverticulitis and bleeding. Diverticular disease is a common cause of significant bleeding from the colon.

Diverticulitis – an infection of the diverticula – may cause one or more of the following symptoms: pain in the abdomen, chills, fever and change in bowel habits. More intense symptoms are associated with serious complications such as perforation (rupture), abscess or fistula formation (an abnormal connection between the colon and another organ or the skin).

The cause of diverticulosis and diverticulitis is not precisely known, but it is more common for people with a low fibre diet. It is thought that a low-fibre diet over the years creates increased colon pressure and results in pockets or diverticula.

Increasing the amount of dietary fibre (grains, legumes, vegetables, etc.) – and sometimes restricting certain foods reduces the pressure in the colon and may decrease the risk of complications due to diverticular disease.

Diverticulitis requires different management. Mild cases may be managed with oral antibiotics, dietary restrictions and possibly stool softeners. More severe cases require hospitalization with intravenous antibiotics and dietary restraints. Most acute attacks can be relieved with such methods.

Surgery is reserved for patients with recurrent episodes of diverticulitis, complications or severe attacks when there’s little or no response to medication. Surgery may also be required in individuals with a single episode of severe bleeding from diverticulosis or with recurrent episodes of bleeding.

Surgical treatment for diverticulitis removes the diseased part of the colon, most commonly, the left or sigmoid colon. Often the colon is hooked up or “anastomosed” again to the rectum. Complete recovery can be expected. Normal bowel function usually resumes in about three weeks. In emergency surgeries, patients may require a temporary colostomy bag. Patients are encouraged to seek medical attention for abdominal symptoms early to help avoid complications.

Haemorrhoids

Haemorrhoids are one of the most common ailments known. More than half the population will develop haemorrhoids, usually after age 30. Millions of Australians currently suffer from haemorrhoids. The average person suffers in silence for a long period before seeking medical care. Today’s treatment methods make some types of haemorrhoid removal much less painful.

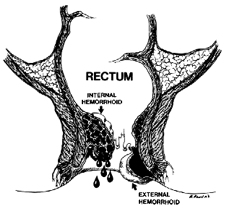

Often described as “varicose veins of the anus and rectum”, haemorrhoids are enlarged, bulging blood vessels in and about the anus and lower rectum. There are two types of haemorrhoids: external and internal, which refer to their location.

External (outside) haemorrhoids develop near the anus and are covered by very sensitive skin. These are usually painless. However, if a blood clot (thrombosis) develops in an external haemorrhoid, it becomes a painful, hard lump. The external haemorrhoid may bleed if it ruptures.

Internal (inside) haemorrhoids develop within the anus beneath the lining. Painless bleeding and protrusion during bowel movements are the most common symptom. However, an internal haemorrhoid can cause severe pain if it is completely “prolapsed” – protrudes from the anal opening and cannot be pushed back inside.

An exact cause is unknown; however, the upright posture of humans alone forces a great deal of pressure on the rectal veins, which sometimes causes them to bulge. Other contributing factors include:

- Aging

- Chronic constipation or diarrhoea

- Pregnancy

- Heredity

- Straining during bowel movements

- Faulty bowel function due to overuse of laxatives or enemas

- Spending long periods of time (e.g., reading) on the toilet

Whatever the cause, the tissues supporting the vessels stretch. As a result, the vessels dilate; their walls become thin and bleed. If the stretching and pressure continue, the weakened vessels protrude.

If you notice any of the following, you could have haemorrhoids:

- Bleeding during bowel movements

- Protrusion during bowel movements

- Itching in the anal area

- Pain

- Sensitive lump(s)

Mild symptoms can be relieved frequently by increasing the amount of fibre (e.g., fruits, vegetables, breads and cereals) and fluids in the diet. Eliminating excessive straining reduces the pressure on haemorrhoids and helps prevent them from protruding. A sitz bath – sitting in plain warm water for about 10 minutes – can also provide some relief .

With these measures, the pain and swelling of most symptomatic haemorrhoids will decrease in two to seven days, and the firm lump should recede within four to six weeks. In cases of severe or persistent pain from a thrombosed haemorrhoid, your physician may elect to remove the haemorrhoid containing the clot with a small incision. Performed under local anaesthesia as an outpatient, this procedure generally provides relief.

Severe haemorrhoids may require special treatment, much of which can be performed on an outpatient basis.

Ligation – the rubber band treatment – works effectively on internal haemorrhoids that protrude with bowel movements. A small rubber band is placed over the haemorrhoid, cutting off its blood supply. The haemorrhoid and the band fall off in a few days and the wound usually heals in a week or two. This procedure sometimes produces mild discomfort and bleeding and may need to be repeated for a full effect.

Injection and Coagulation can also be used on bleeding haemorrhoids that do not protrude. Both methods are relatively painless and cause the haemorrhoid to shrivel up.

Haemorrhoidectomy – surgery to remove the haemorrhoids – is the most complete method for removal of internal and external haemorrhoids. It is necessary when (1) clots repeatedly form in external haemorrhoids; (2) ligation fails to treat internal haemorrhoids; (3) the protruding haemorrhoid cannot be reduced; or (4) there is persistent bleeding. A haemorrhoidectomy removes excessive tissue that causes the bleeding and protrusion. It is done under anaesthesia using either sutures or staplers, and may, depending upon circumstances, require hospitalization and a period of inactivity. Laser haemorrhoidectomies do not offer any advantage over standard operative techniques. They are also quite expensive, and contrary to popular belief, are no less painful.

No. There is no relationship between haemorrhoids and cancer. However, the symptoms of haemorrhoids, particularly bleeding, are similar to those of colorectal cancer and other diseases of the digestive system. Therefore, it is important that all symptoms are investigated by a physician specially trained in treating diseases of the colon and rectum and that everyone 50 years or older undergo screening tests for colorectal cancer. Do not rely on over-the-counter medications or other self-treatments. See a colorectal surgeon first so your symptoms can be properly evaluated and effective treatment prescribed.

Pilonidal Disease

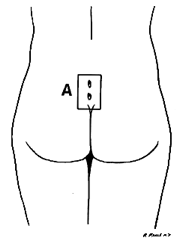

Pilonidal disease is a chronic infection of the skin in the region of the buttock crease (Figure 1). The condition results from a reaction to hairs embedded in the skin, commonly occurring in the cleft between the buttocks. The disease is more common in men than women and frequently occurs between puberty and age 40. It is also common in obese people and those with thick, stiff body hair.

Symptoms vary from a small dimple to a large painful mass. Often the area will drain fluid that may be clear, cloudy or bloody. With infection, the area becomes red, tender, and the drainage (pus) will have a foul odour. The infection may also cause fever, malaise, or nausea.

There are several common patterns of this disease. Nearly all patients have an episode of an acute abscess (the area is swollen, tender, and may drain pus). After the abscess resolves, either by itself or with medical assistance, many patients develop a pilonidal sinus. The sinus is a cavity below the skin surface that connects to the surface with one or more small openings or tracts. Although a few of these sinus tracts may resolve without therapy, most patients need a small operation to eliminate them.

A small number of patients develop recurrent infections and inflammation of these sinus tracts. The chronic disease causes episodes of swelling, pain, and drainage. Surgery is almost always required to resolve this condition.

The treatment depends on the disease pattern. An acute abscess is managed with an incision and drained to release the pus, and reduce the inflammation and pain. This procedure usually can be performed in the office with local anaesthesia. A chronic sinus usually will need to be excised or surgically opened.

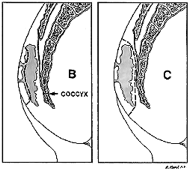

Complex or recurrent disease must be treated surgically. Procedures vary from unroofing the sinuses to excision (Figure 2) and possible closure with flaps. Larger operations require longer healing times. If the wound is left open, it will require dressing or packing to keep it clean. Although it may take several weeks to heal, the success rate with open wounds is higher. Closure with flaps is a bigger operation that has a higher chance of infection; however, it may be required in some patients. Your surgeon will discuss these options with you and help you select the appropriate operation.

If the wound can be closed, it will need to be kept clean and dry until the skin is completely healed. If the wound must be left open, dressings or packing will be needed to help remove secretions and to allow the wound to heal from the bottom up.

After healing, the skin in the buttocks crease must be kept clean and free of hair. This is accomplished by shaving or using a hair removal agent every two or three weeks until age 30. After age 30, the hair shaft thins, becomes softer and the buttock cleft becomes less deep.

Laparoscopic Appendicectomy

What is the appendix?

The appendix produces a bacteria destroying protein called immunoglobulins which help fight infection in the body. Its function, however, is not essential. People who have had appendicectomies do not have an increased risk toward infection. Other organs in the body take over this function once the appendix has been removed.

Appendicitis is one of the most common surgical problems. Treatment requires an operation to remove the infected appendix. Traditionally, the appendix is removed through an incision in the right lower abdominal wall.

In most laparoscopic appendicectomies, surgeons operate through 3 small incisions (each 1-2cm) while watching an enlarged image of the patient’s internal organs on a television monitor. In some cases, one of the small openings may be lengthened to 2-3cm to complete the procedure.

Results may vary depending upon the type of procedure and patient’s overall condition. Common advantages are:

- Less postoperative pain

- May shorten hospital stay

- May result in a quicker return to bowel function

- Quicker return to normal activity

- Better cosmetic results

Although laparoscopic appendicectomy has many benefits, it may not be appropriate for some patients. Early, non-ruptured appendicitis usually can be removed laparoscopically. Laparoscopic appendicectomy is more difficult to perform if there is advanced infection or the appendix has ruptured. A traditional, open procedure using a larger incision may be required to safely remove the infected appendix in these patients.

The words “laparoscopic” and “open” appendicectomy describes the techniques a surgeon uses to gain access to the internal surgery site.

Most laparoscopic appendicectomies start the same way. Using a cannula (a narrow tube-like instrument), the surgeon enters the abdomen. A laparoscope (a tiny telescope connected to a video camera) is inserted through a cannula, giving the surgeon a magnified view of the patient’s internal organs on a television monitor. Several other cannulas are inserted to allow the surgeon to work inside and remove the appendix. The entire procedure may be completed through the cannulas or by lengthening one of the small cannula incisions. A drain may be placed during the procedure. This will be removed before you leave the hospital.

In a small number of patients the laparoscopic method is not feasible because of the inability to visualize or handle the organs effectively. When the surgeon feels that it is safest to convert the laparoscopic procedure to an open one, this is not a complication, but rather sound surgical judgment. Factors that may increase the possibility of converting to the “open” procedure may include:

- Extensive infection and/or abscess

- A perforated appendix

- Obesity

- A history of prior abdominal surgery causing dense scar tissue

- Inability to visualize organs

- Bleeding problems during the operation

The decision to perform the open procedure is a judgment decision made by your surgeon either before or during the actual operation. The decision to convert to an open procedure is strictly based on patient safety.

Anal Fissure

An anal fissure (fissure-in-ano) is a small, oval shaped tear in skin that lines the opening of the anus. Fissures typically cause severe pain and bleeding with bowel movements. Fissures are quite common in the general population, but are often confused with other causes of pain and bleeding, such as haemorrhoids.

The typical symptoms of an anal fissure include severe pain during, and especially after, a bowel movement, lasting from several minutes to a few hours. Patients may also notice bright red blood from the anus that can be seen on the toilet paper or on the stool. Between bowel movements, patients with anal fissures are often relatively symptom-free. Many patients are fearful of having a bowel movement and may try to avoid defecation secondary to the pain.

Fissures are usually caused by trauma to the inner lining of the anus. Patients with tight anal sphincter muscles (i.e., increased muscle tone) are more prone to developing anal fissures. A hard, dry bowel movement is typically responsible, but loose stools and diarrhoea can also be the cause. Following a bowel movement, severe anal pain can produce spasm of the anal sphincter muscle, resulting in a decrease in blood flow to the site of the injury, thus impairing healing of the wound. The next bowel movement results in more pain, anal spasm, decreased blood flow to the area, and the cycle continues. Treatments are aimed at interrupting this cycle by relaxing the anal sphincter muscle to promote healing of the fissure.

Other, less common, causes include inflammatory conditions and certain anal infections or tumours. Anal fissures may be acute (recent onset) or chronic (present for a long period of time). Chronic fissures may be more difficult to treat, and may also have an external lump associated with the tear, called a sentinel pile or skin tag, as well as extra tissue just inside the anal canal (hypertrophied papilla) .

The majority of anal fissures do not require surgery. The most common treatment for an acute anal fissure consists of making the stool more formed and bulky with a diet high in fibre and utilization of over-the-counter fibre supplementation (totalling 25-35 grams of fibre/day). Stool softeners and increasing water intake may be necessary to promote soft bowel movements and aid in the healing process. Topical anaesthetics for pain and warm tub baths (sitz baths) for 10-20 minutes several times a day (especially after bowel movements) are soothing and promote relaxation of the anal muscles, which may help the healing process.

Other medications (such as nitroglycerin, nifedipine, or diltiazem) may be prescribed that allow relaxation of the anal sphincter muscles. Your surgeon will go over benefits and side-effects of each of these with you. Narcotic pain medications are not recommended for anal fissures, as they promote constipation. Chronic fissures are generally more difficult to treat, and your surgeon may advise surgical treatment.

Fissures can recur easily, and it is quite common for a fully healed fissure to recur after a hard bowel movement or other trauma. Even when the pain and bleeding have subsided, it is very important to continue good bowel habits and a diet high in fibre as a lifestyle change. If the problem returns without an obvious cause, further assessment is warranted.

A fissure that fails to respond to conservative measures should be re-examined. Persistent hard or loose bowel movements, scarring, or spasm of the internal anal muscle all contribute to delayed healing. Other medical problems such as inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease), infections, or anal tumours can cause symptoms similar to anal fissures. Patients suffering from persistent anal pain should be examined to exclude these symptoms. This may include a colonoscopy or an exam in the operating room under anaesthesia.

Surgical options for treating anal fissure include Botulinum toxin (Botox®) injection into the anal sphincter and surgical division of a portion of the internal anal sphincter (lateral internal sphincterotomy). Both of these are performed typically as outpatient, same-day procedures, or occasionally in the office setting. The goal of these surgical options is to promote relaxation of the anal sphincter, thereby decreasing anal pain and spasm, allowing the fissure to heal. Botox® injection results in healing in 50-80% of patients, while sphincterotomy is reported to be over 90% successful. If a sentinel pile is present, it may be removed to promote healing of the fissure. All surgical procedures carry some risk, and a sphincterotomy can rarely interfere with one’s ability to control gas and stool. Your colon and rectal surgeon will discuss these risks with you to determine the appropriate treatment for your particular situation.

It is important to note that complete healing with both medical and surgical treatments can take up to approximately 6-10 weeks. However, acute pain after surgery often disappears after a few days. Most patients will be able to return to work and resume daily activities in a few short days after the surgery.

No. Persistent symptoms, however, need careful evaluation since other conditions other than an anal fissure can cause similar symptoms. Your colon and rectal surgeon may request additional tests, even if your fissure has successfully healed. A colonoscopy may be required to exclude other causes of rectal bleeding.

Anal Abscess/Fistula

An anal abscess is an infected cavity filled with pus found near the anus or rectum.

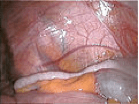

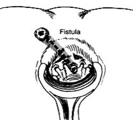

An anal fistula (also called fistula-in-ano) is frequently the result of a previous or current anal abscess, occurring in up to 50% of patients with abscesses. Normal anatomy includes small glands just inside the anus. Occasionally, these glands get clogged and potentially can become infected, leading to an abscess. The fistula is a tunnel that forms under the skin and connects the infected glands to the abscess. A fistula can be present with or without an abscess and may connect just to the skin of the buttocks near the anal opening. Other situations that can result in a fistula include Crohn’s disease, radiation, trauma and malignancy.

The abscess is most often a result of an acute infection in the internal glands of the anus. Occasionally, bacteria, faecal material or foreign matter can clog the anal gland and create a condition for an abscess cavity to form. Other medical conditions can make these types of infections more likely.

After an abscess drains on its own or has been drained (opened), a tunnel (fistula) may persist, connecting the infected anal gland to the external skin. This typically will involve some type of drainage from the external opening and occurs in up to 50% of abscesses. If the opening on the skin heals when a fistula is present, a recurrent abscess may develop.

A patient with an abscess may have pain, redness or swelling in the area around the anal area. Fatigue, general malaise, as well as accompanying fever or chills are also common. Similar signs and symptoms may be present when patients have a fistula, with the addition of possible irritation of the perianal skin or drainage from an external opening.

No. Most anal abscesses or fistula-in-ano are diagnosed and managed on the basis of clinical findings. Occasionally, additional studies such as ultrasound, CT scan, or MRI can assist with the diagnosis of deeper abscesses or the delineation of the fistula tunnel to help guide treatment.

The treatment of an abscess is surgical drainage under most circumstances. An incision is made in the skin near the anus to drain the infection. This can be done in a doctor’s office with local anaesthetic or in an operating room under deeper anaesthesia. Hospitalization may be required for patients prone to more significant infections such as diabetics or patients with decreased immunity.

Antibiotics alone are a poor alternative to drainage of the infection. For uncomplicated abscesses, the addition of antibiotics to surgical drainage does not improve healing time or reduce the potential for recurrences. There are some conditions in which antibiotics are indicated, such as for patients with compromised or altered immunity, some cardiac valvular conditions or extensive cellulitis. A comprehensive discussion of your past medical history and a physical exam are important to determine if antibiotics are indicated.

Surgery is almost always necessary to cure an anal fistula. Although surgery can be fairly straightforward, it may also be complicated, occasionally requiring staged or multiple operations. Consider identifying a specialist in colon and rectal surgery who would be familiar with a number of potential operations to treat the fistula.

The surgery may be performed at the same time as drainage of an abscess, although sometimes the fistula doesn’t appear until weeks to years after the initial drainage. If the fistula is straightforward, a fistulotomy may be performed. This procedure involves connecting the internal opening within the anal canal to the external opening, creating a groove that will heal from the inside out. This surgery often will require dividing a small portion of the sphincter muscle which has the unlikely potential for affecting the control of bowel movements in a limited number of cases.

Other procedures include placing material within the fistula tract to occlude it or surgically altering the surrounding tissue to accomplish closure of the fistula, with the choice of procedure depending upon the type, length, and location of the fistula. Most of the operations can be performed on an outpatient basis, but may occasionally require hospitalization.